Natural Burial Ground

A fieldstone grave marker at Ramsey Creek, a conservation burial ground in Westminster, SC.

After I visited the conservation burial ground at Ramsey Creek, I never saw a cemetery the same way again. Dr. Billy Campbell and his wife Kimberley of Westminster, South Carolina, own and manage Ramsey Creek under the corporate name Memorial Ecosystems. The Campbells were the first to introduce conservation burial to the United States. They work to preserve land and restore habitat while providing a socially responsible burial option. Their credo is "Dust to dust."

With 70 wooded acres of rambling trails, wild flowers, cliffs and water ways, it may not be apparent at first that there are more than 250 people buried at Ramsey Creek. The graves are inconspicuous mounds sometimes marked by humble fieldstones. Hikers taken by the beauty of the scenery may notice only a few of the plots.

The wooded trails at Ramsey Creek.

With conservation burial (also called green burial, natural burial, or ecological burial), the body is prepared without embalming and buried in a biodegradable coffin, such as one made of cardboard or unfinished pine. At Ramsey Creek, families may also bury their loved one without a coffin, in a shroud. Most families work with a funeral director to file the necessary paperwork and transport the body from the place of death to Ramsey Creek. Some of Ramsey Creek's customers have home funerals and bring the body to Ramsey Creek themselves.

"We had a guy who brought his mother here, down from Virginia, in the back of his Suburban," said Kimberley. "Another family came up here from Georgia. They built a pine casket and placed their mother in it, and they brought her up in a trailer."

The staff at Ramsey Creek digs holes with shovels, rather than machines, to minimize disruption to the soil. Families receive native plants to place into the tops of burial mounds after the grave is closed again.

A burial at Ramsey Creek is a hands-on experience. Families assist in lowering their loved one's coffin or shrouded body into the grave and they help fill the grave with soil. The Campbells provide native plants for families to place into the tops of the burial mounds. According to the Campbells, families feel spiritually connected to the burial ritual when they are involved in its making. It also comforts many families to know that as their loved ones return to the earth, their bodies nourish plant life.

The 19th-century chapel at Ramsey Creek.

Ramsey Creek offers the use of a 19th-century chapel for ceremonies and gatherings. The Campbells purchased the building to save it from demolition and had it moved to Ramsey Creek from a town nearby. "We rent the chapel for weddings and community events as well as funerals," said Kimberley.

Some families who have had funerals at Ramsey Creek return year after year for family reunions. And because Ramsey Creek is one of few natural burial grounds in the U.S., their customers are willing to drive long distances to get there. "One guy came from [western] Tennessee, which is about a nine hour drive," said Kimberley.

Wildflowers over a grave at Ramsey Creek.

What is it about Ramsey Creek that helps people achieve meaningful funerals? Kimberley believes it's partially the control families feel in taking part in the ritual themselves. Many of Ramsey Creek's funeral customers report back to the Campbells, saying that services at Ramsey Creek were especially memorable for them. At times, funerals have even been celebrational.

"We have a guy buried here who used to have an annual wienie roast for all his friends and family," said Kimberley, "So at his funeral, they had a huge wienie roast in his honor. And it was a party."

Kimberley also commented on the universal spirituality about nature. One visit to Ramsey Creek may be all it takes to convince people, regardless of their beliefs, to try a natural burial. "Sometimes all it takes is good old nature," said Kimberley, "It comes down to that."

Military Honors

Chris McCampbell admiring his grandfather's gravestone at Arlington National Cemetery.

My friends Chris and Sandy McCampbell and I visited Arlington National Cemetery during the Christmas season, when the cemetery staff puts wreaths on every soldier's grave. Chris has two relatives buried at Arlington, an honor bestowed on few Americans. Since its inception during the Civil War, Arlington has become the final resting place for more than 400,000 men and women of distinguished public service. Every year, over 4 million people visit. Of America's 131 national cemeteries, Arlington is seen as the premier military burial ground. It is a tourist attraction and a national shrine.

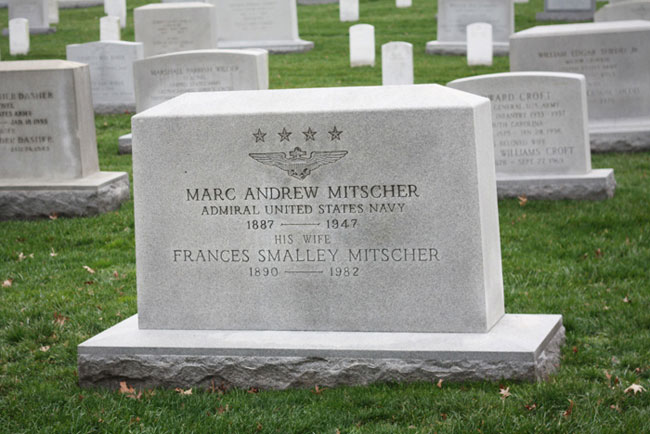

The gravestone for Admiral Marc Mitscher, Chris McCampbell's great-great-uncle.

Chris and his wife Sandy grew up in San Diego in families who gave several generations of service to the Navy. Chris' grandmother is especially proud of their military heritage. She filled a wall in her home with newspaper clippings, old pictures and other artifacts to memorialize Admiral Marc Mitscher, her uncle, and Chris' great-great-uncle, buried at Arlington. "The Navy is a big deal to my grandmother," said Chris, "She looked up to Uncle Marc her whole life. And, she later married a Navy man."

"I'm proud that Granddad is buried beside so many who fought for our country."

Our visit that day was the second time Chris and Sandy visited Arlington. "The first time we came, it was an emotional experience," said Chris. As we stood on the patch of grass above his grandfather's grave, we talked about the significance of military burial. "I'm proud that Granddad is buried beside so many who fought for our country," said Chris.

The gravestone for Captain David McCampbell, Chris' Granddad.

Capt. David McCampbell, or Granddad, as Chris calls him, was nicknamed the "Ace of Aces" for his skill as a fighter pilot during World War II. "In one day, he shot down nine enemy planes," said Chris. For his prowess, Capt. McCampbell was awarded the highest military decoration given by the US Government, the Medal of Honor. The Navy also named a ship after him. As Chris and I spoke on that cold afternoon at Arlington, the USS McCampbell was somewhere at work in the southern waters of the Pacific Ocean.

"I like Granddad's gold," said Chris as he ran his fingers over the lettering on his grandfather's gravestone. The letters were filled with a golden pigment, a little extra flare for Capt. McCampbell's distinction. "What's cool about these gravestones is that they're all so similar," said Chris, "But within these limitations, you get some idea of the individual."

Chris didn't attend his grandfather's funeral. A few years after Captain McCampbell's passing, Chris and his father, were guests of honor at the commissioning of the USS McCampbell.

Chris keeps a hat that belonged to his grandfather and he suspects that someday his father will pass down the bounty of artifacts related to Capt. McCampbell's life. Chris told me that he'd like to fill a wall in his home with pictures and newspaper clippings about his grandfather, the way his grandmother did for Admiral Mitscher.

"I didn't know him well when he was alive," said Chris about his grandfather, "But by memorializing him, I'm getting to know him now."

Personal Rituals

In one of the last moments that Bob C, of Baltimore, Maryland, shared with his father, the older man was too feeble to take part in his favorite relaxing activity: smoking a cigar. "I never smoked before, but I told him that I'd smoke his cigar for him," said Bob. "Now, I smoke a cigar about once a month, just to take time to remember my dad."

Robin Carter, of Columbus, Ohio says there isn't a day that goes by that she doesn't think about her mother. "I talk to her frequently for various reasons. I try to visit her grave as often as I can... One thing I do is play the lottery on her birthday." Robin's mother played the lottery every week when she was alive. It was one of her favorite things to do. "She always played a certain set of numbers so I play those," said Robin with a smile. "I haven't won yet."

Kelcey Towell, of Little Rock, Arkansas, remembers her grandmother as an elegant woman who loved fine things. "She left me this little ashtray with birds on it," said Kelcey, "I put my earrings in it at night before I go to bed."

Many people have private ways that they remember someone they love. Little mementos or everyday activities keep a person's memory an active part of regular life.

A Music Box Urn

This urn is a simple walnut box that plays "Oh Susanna" when the handle is turned.

When I was a little girl, my grandfather taught me the song, "Oh Susanna." I remember giggling when he sang, "It rained so hard the day I left. The weather, it was dry." His voice was a squeaky tenor and he had no teeth. "It sunned so hot, I froze to death, Susanna don't you cry," he sang with a lisp which I found, even then, so comical and sweet.

Now that my grandfather is near the end of his life, my mother and I have discussed his final plans. We're going to spread most of his ashes at his favorite fishing spot. But, I also designed a small urn to hold a portion of his cremated remains.

I met a funeral director in Crown Point, Indiana who told me that people often purchase urns at the initial point of loss only to find out later that they can't stand living with them. For some people, urns prevent them from surmounting grief. Standard size urns take up a lot of space. They're too noticable, too dominating in a living environment. What bothers me most about urns is that they just sit there.

I wanted to make a place in my home to interact with the memory of my grandfather. This urn is an analog music box, old school like my grandpa, that plays our special song. The speed at which I turn the crank affects how happy or sad the song sounds. And, the urn is only 6x9 centimeters in size, so it fits comfortably in my home.

Sea Burial

The Captain Tom, docked on the Chesapeake Bay.

"When you go to sea, you go to work, baby,"

Captain Tom Hallock, owner of Life Beyond Sea Burial in Baltimore, Maryland, takes families out on the Chesapeake Bay in his boat, The Captain Tom, to scatter the remains of their loved ones. Hallock believes that the sea is the ideal final resting place because cremated remains nourish life in the ocean. He calls this "going to work."

"A lot of people don't know about sea burial," said Capt. Hallock, "But if you ask me, there's no better way to go." Sea burial is a compelling choice for many families. The total cost of a sea burial, with separate fees for the crematory operator, is significantly less than a conventional funeral. Some people have said that spending a few hours at sea is better for the spirit than the typical funeral home viewing. And, according to Capt. Hallock, families can take comfort that their loved ones are at work in the ocean.

Most companies that provide sea burials only handle cremated remains. Federal regulations require that whole body sea burials happen far offshore, where waters are unprotected. For this reason, whole body sea burials are the privilege of the U.S. Navy. Many sea burial companies, like Life Beyond, will accept cremated remains sent by mail and scatter them for families at a lower price.

For obvious reasons, scattering remains in the ocean leaves no permanent marker. For those who want a permanent place in the ocean, there is a newer funeral trend to consider. Memorial Reefs, like the ones owned by Eternal Reefs, rebuild habitat for marine life. Memorial reefs are modules, called "reef balls," made from a combination of concrete and cremated remains. People who inter their loved ones in memorial reefs can take part in casting their loved one's reef ball and they can attend a dedication ceremony. After the reef ball is in place within the memorial reef, families can visit their loved one's grave by scuba diving. Memorial reef interment can range in price from $2500 to $6500, on top of the cost of cremation.

One final note about sea burial: Throughout the course of this project, I met a number of people who seemed interested in Norse or Viking funerals. More than a few people asked me if it's legally possible to have a ship burial, in which the deceased person is placed on a boat, set aflame, and pushed out into the open ocean. Since ship burials are harmful to the environment, and quite dangerous for fishermen, sailors, and other friends of the sea, it is not legal in the United States to perform such a ritual.