Elegy: A Memorial App Concept

Elegy is a concept for an app that allows people to make curated memorial albums and share them via social media. Elegy albums include some of the standard items seen at a conventional funeral, such as a guestbook, obituary, and slideshow. The app also allows users to share written stories and videos. Lastly, Elegy users can make custom sections to share more personalized items. For example, if the deceased was a great cook, friends and family could include recipes in the album.

I designed this app in response to conversations I had about social media and memorial. Facebook memorial pages are increasing in popularity. While many people acknowledge the benefit of sharing with so many people at one time, they also say that death notices and memorial pages in this context can be jarring. With Elegy, I propose a designated space for memorializing that integrates with popular social media platforms.

Video soundtrack by Jason Shaw.

A Good Obituary

A good obituary is a character sketch, not a resume.

I interviewed Maureen O'Donnell, a journalist for the Chicago Sun-Times, who has been writing obituaries for years. In her opinion, the best obituaries tell a unique story about the deceased person's life while providing a sense of time and place. "I try to educate the readers and make [the obituary] more of a history lesson," said O'Donnell of her approach to obituary writing.

O'Donnell's favorite thing about writing obituaries is finding a unique entry point. She looks for an interesting fact about someone's life and shapes her story around that. She has written obituaries for the inventor of Lemonheads, a man who survived two grizzly bear attacks before dying peacefully in his sleep at an old age, and the world's top expert on fountain pens. O'Donnell also enjoys connecting with the families of her subjects. "It's the only job at the newspaper where you get thank you notes," she said.

Unlike a death notice, which families pay to have printed in newspapers, obituaries are news stories written by professional journalists at no cost to the deceased person's family. However, many people write long-form stories about a deceased person's life for private use. These obituaries, though they are not always published in the news, are sometimes given as tokens to guests at funerals, printed in the funeral program, or read out loud during the memorial service.

How to Write an Obituary

It would be in poor taste to suggest an easy-to-follow template for writing obituaries, given that there seems to be a desire for more personalized memorials. But Don Fry, of the Poynter Institute, offers detailed guidelines for writing one's own obituary. His article was written for journalists, but non-journalists can also benefit from his wisdom.

Fry quotes Jim Nicholson, a former writer for the Philadelphia Daily News who made it his practice to write feature obituaries on ordinary people selected at random. Nicholson's belief was, "If you're a good enough reporter, everybody's interesting."

A good obituary is a character sketch, not a resume. Fry encourages us to prioritize anecdotes and personal recollections while moving items like age, date of birth, and cause of death to the background.

Like any project, starting a good obituary requires a little research. To get started, do what professionals like Maureen O'Donnell do: talk to several of the deceased person's friends and family members. Ask them to share their favorite memories. Write down some of the most noteworthy quotes. Look for an interesting entry point and shape the story around that.

If you're writing your own obituary, you can take advice from Don Fry, "Write a few rich paragraphs in the third person, answering this question: 'What do I want people to remember about me?'"

Harry de Quetteville in his Telegraph article, "The Art of the Obituary," says that the best way to start writing an obituary is to assemble as much information as possible from as many sources as possible before "simmering it all down into a narrative."

Like every good news story, an obituary should have a memorable ending. A friend of mine, Lisa Holton, who is also a professional writer and a former Sun-Times journalist, said to me, "The best obits end with a bit of a surprise or a little tidbit that no one ever really knew about the person. It doesn't need to be maudlin or sappy. It just needs to fit the person and leave the reader with a bit of wow, if possible."

Beyond the Sympathy Card

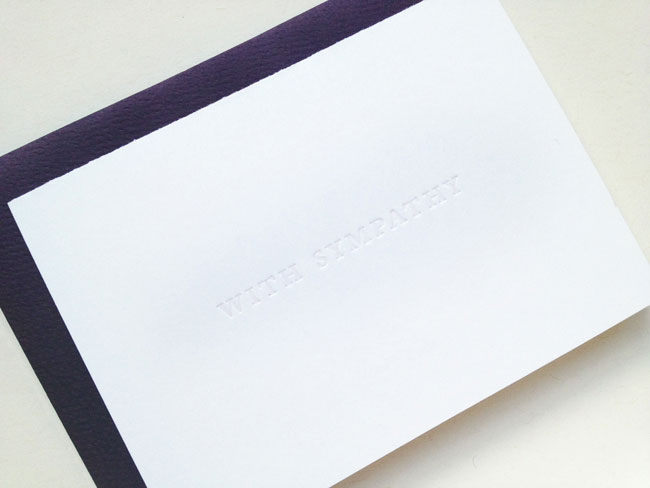

Many people appreciate sympathy cards that include the sincere condolences of the sender. Sympathy cards are easy to find in supermarkets and stationery shops. These cards often include a poem or a pre-printed message which can help people express their feelings when they aren't sure what to say. The downside to sending an off-the-shelf sympathy card is that the grieving recipient may end up with several cards that carry the same message and design. Perhaps a better option is a card that is simply designed, produced with quality materials, and blank inside, so that the sender's message can come from the heart.

This sympathy card is letterpress printed on a crisp, soft sheet of paper and is devoid of expression except the writer's.

In writing a sympathy card, it's best to speak from the heart, to be loving and concise, but not to indulge in cliché responses to someone's grief. A sympathy card is an ideal place to share a beloved memory about the person who passed away.

The Funeral Consumers Alliance, a nonprofit organization dedicated to helping people plan dignified and affordable funerals, offers guidelines for supporting people in grief. Among these guidelines are suggestions on what not to do or say. The guidelines also read:

"Relatives, friends and neighbors are often supportive at the time of a death and during the wake and funeral... But after the funeral, the bereaved sometimes wonder where their friends have gone."

This collection of cards is a system for sending support over a period of time.

Grieving people need continued support after the funeral is over. A single sympathy card is nice, but perhaps a correspondence program is better. Inspired by the Jewish tradition of Shiva, I designed the sympathy cards above to be sent over a period of time.

Judaism provides a structured approach to mourning that serves to bring grieving relatives through the tragedy of their loss back into regular life. Mourners receive ample community support, which is constant, at first, but dissipates over time. The circle motif on these cards also dissipates with time and the envelope color shifts from black to gray to light gray. The packaging includes spaces to keep track of when the first card was sent and when to send the next cards.

Story Inside: Collecting as Memorial

I asked a group of people, who live in different places all over the world, to tell a story about someone they love by placing objects inside a mason jar. I made this zine with their responses.

Collecting is a form of storytelling. Many people save objects that remind them of people they love. I asked a group of volunteers, who live in different places all over the world, to tell a story about someone they love by placing objects inside a mason jar. Each contributor also sent me a few words to describe why they chose the objects they did.